The United States Life-Saving Service

Next | Previous | Return to Start

|

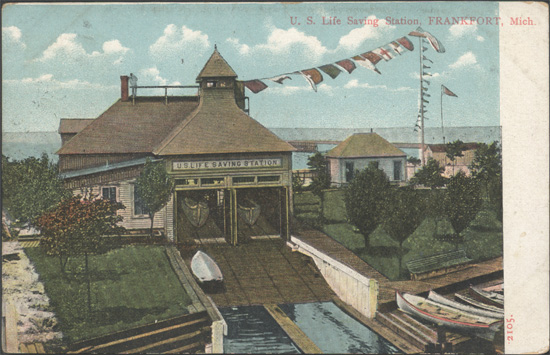

In 1871, the Federal Government formed the United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS) to operate primarily along the Atlantic coast. In 1874 when commercial shipping was booming in the Great Lakes, federal legislation expanded the USLSS to this region. In 1915, the USLSS merged with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service to form the United States Coast Guard. Life-Saving Stations Near ArcadiaIn the Arcadia area, the nearest U. S. Life-Saving Service stations were in Manistee and Frankfort. The Manistee station was built in 1879. Construction began on the Frankfort station in 1886. When ships were in trouble in the Arcadia area, if there was time, life-saving crews were dispatched from one or both of these stations. These brave men saved lives by battling cold Lake Michigan surf in light boats to remove stranded crew from sinking ships. |

|

|

What Crews Did in EmergenciesWhen a ship was in trouble, life-saving crews had several ways to help.

|

|

|

Practice, Practice, PracticeA life-saving station crew was constantly practicing, learning each other's skills, and watching for trouble around the clock. For example, USLSS regulations required beach apparatus drills on Mondays and Thursdays, and lifeboat and surfboat practice were required on Tuesdays, weather and circumstances permitting. For all this practice and danger, the most senior member, the keeper, earned $800 per year in 1880 and $1,000 per year in 1912 not including uniforms. |

|

|

|

|

|

Instructions to Mariners These are excerpts "Instructions to Mariners in Case of Shipwreck," published in the 1901 Annual Report of the USLSS. "...All services are performed by the life-saving crews without other compensation than their wages from the Government, and they are strictly forbidden to solicit or receive rewards. "Destitute seafarers are provided with food and lodgings at the nearest station by the Government as long as necessarily detained by the circumstance of shipwreck. "The station crews patrol the beach from two to four miles each side of their stations four times between sunset and sunrise, and if the weather is foggy the patrol is continued through the day. "Each patrolman carries Coston signals. Upon discovering a vessel standing into danger he ignites one of them, which emits a brilliant red flame of about two minutes' duration, to warn her off, or, should the vessel be ashore, to let the crew know that they are discovered and assistance is at hand. "If the vessel is not discovered by the patrol immediately after striking, rockets or flare-up lights should be burned on board, or, if the weather be foggy, guns should be fired to attract attention, as the patrolman may be some distance away on the other part of his beat. "Masters are particularly cautioned, if they should be driven ashore anywhere in the neighborhood of the stations, especially on any of the sandy coasts, where there is not much danger of vessels breaking up, to remain on board until assistance arrives, and under no circumstances should they attempt to land through the surf in their own boats until the last hope of assistance from the shore has vanished. Often when comparatively smooth at sea a dangerous surf is running, which is not perceptible three or four hundred yards offshore, and the surf, when viewed from a vessel, never appears so dangerous as it is. Many lives have unnecessarily been lost by the crews of stranded vessels being thus deceived and attempting to land in the ships' boats. "The difficulties of rescue by operations from the shore are greatly increased when the anchors are let go after entering the breakers, as is frequently done, and the chances of saving life are correspondingly lessened." |

|